This article introduces the characteristics of production in the long run by explaining and visualizing on a graph how firms move from the short run production to the long run production.

It describes how firms can experience both internal economies of scale and internal diseconomies of scale. As well as, it describes how firms can experience both external economies of scale and external diseconomies of scale. Also, it explains with examples factors that economies of scale and diseconomies of scale could have on the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve.

Finally, this post describes and analyzes relationship between average costs in the short run and average costs in the long run.

Production in the long run

In the long run, all factors of production are variable. This means that there are no Fixed Costs (FC) in the long run, e.g. rent must be paid or new equipment needs to be purchased and they may cost differently from before.

The Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve represents total cost of the business. The two diagrams below show the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve. The diagrams appear different as there is more than one way to illustrate the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC).

Diagram 1: It shows the Optimal Level of Production, which occurs between where the lowest cost starts and ends. The beginning of this output range is called the Minimum Efficient Scale (MES).

Diagram 2: It shows that productive efficiency occurs at the lowest point of the U-shaped curve.

Economies of scale

Economies of scale are the factors that cause costs to be lower in large scale operations than in small ones. Doubling output does not mean the doubling of costs. Therefore, the cost per unit, or average cost, is cheaper for the larger company.

Economies of scale occur when average costs decrease as output rises. Average costs fall in the long run because of economies of scale. Economies of scale can be either internal or external.

TIP: If the business is managed well, producing a greater number of units can result in economies of scale, hence saved costs.

Diseconomies of scale

On the other hand, diseconomies of scale are those factors causing higher costs per unit as output increases (causes of inefficiency in large organizations). They occur because of management inability to handle the large scale of the business. Sometimes in growing firms the owner is unwilling to give up power leading to a larger centrally planned organization with slow decisions. Even with decentralization management can have difficulty with communication and co-ordination.

Diseconomies of scale occur when average costs increase as output rises. Average costs rise in the long run because of diseconomies of scale. Diseconomies of scale can be either internal or external.

TIP: If the business is not managed well, diseconomies of scale can occur leading to higher costs due to inefficiency caused by poor communication and co-ordination.

Internal economies of scale & Internal diseconomies of scale

A movement along the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve occurs because of internal economies of scale and internal diseconomies of scale. Average costs may change because of internal factors. These internal factors are within the control of the firm.

A. Internal economies of scale

Internal economies of scale are associated with the output of a company and cause a movement along the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve. If economies of scale are internal to the firm, the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve is falling. There are several ways a company can achieve internal economies of scale, as detailed below.

1. Purchasing. A company making a larger amount of goods should be able to benefit from bulk buying. Bulk buying means purchasing large enough quantities to secure a lower price per unit. Buying larger quantities can also help a relationship form with the producer of what is bought. This can result in a company buying direct from producers, cutting out the middleman (wholesaler, retailer, etc). Having this relationship can increase consumer sovereignty for the company because they can make more specific demands about quality service and other specifications.

2. Technical. As a company grows it may be more cost effective to invest in more advanced production machinery. Additionally, smaller firms may not use equipment to maximum potential. Perhaps an office has a conference room which is used once a week. That room takes up space and therefore rent money. Expanding and using the room and equipment inside more often will lead to individual unit costs decreasing.

Example 1: A small chocolate producer has 3 production lines with 5 workers each. They produce 15,000 units per week. Wages are 3,000 per week. The company has been successful and wants to enlarge. They could purchase another machine which would result in production increasing to 20,000 units per week and wages increasing to 4,000 per week, including the cost of 5 extra workers. Alternatively, they could purchase 2 new machines and sell their old out-of-date production lines. These newer machines are faster and could produce 10,000 units per week each and also require 5 workers each. Production would then increase to 20,000 per week and wages would decrease to 2,000 per week. The jobs of 5 workers are made redundant, meaning that these jobs no longer exists.

3. Managerial. As a company becomes larger, managers specializing in different disciplines (e.g. marketing, finance, production) will take over all the major decisions of that discipline. This specialization allows for quicker, better judged decisions which ultimately lead to better productivity and saved costs. It is not only managers who can benefit from this specialization – normal employees in the workforce are also able to specialize. Specialization amongst the workforce is called division of labor. Division of labor involves breaking a job down into small repetitive fragments, each of which can be done at speed by workers with little formal training. If one man works on a production line completes every part of the production process, he is slower than several individual workers sharing one complete task between them.

a. Strengths of divisions of labor: Little training is needed and the work is relatively unskilled – it is therefore cheap. A specialized worker is far more productive. This is because a worker becomes highly proficient at their type of work. They can also be put to work at that which they do best. Division of labor allows workers to have specialized equipment. By allowing them to do their job better with special gear, a worker can be even more productive. The fact that not all workers will need specialized equipment adds to the savings experienced by the firm.

b. Weaknesses of divisions of labor: Unfortunately, jobs which are broken up into small parts can be very boring due to the repetitive nature. This can result in alienation from the workforce. Alienation is to feel isolated and lonely. Alienation results in low motivation, ultimately having a negative effect on production.

4. Marketing. Larger companies have more marketing options to choose from. A small company may not find it cost effective to use TV or a national newspaper for their promotional efforts. The advertising costs of selling 10 million units through TV are the same as selling 1 million units using the same medium. Therefore the average costs of advertising are less for a large firm. It is also true that a large firm will find it easier to gain publicity because of its current reputation.

5. Financial. Large companies find borrowing easier. Banks perceive them to be less risky compared to smaller companies. Not only will they receive a loan more easily, but they have the ability to bargain for a lower rate of interest to pay; thus reducing the cost of borrowing. Large firms also have a greater range of options for sources of finance. For example, only large firms known as public limited companies can raise finance via the stock market.

6. Risk bearing. A larger company can be safer from failure by having a more diversified product range. Examples include Sony producing electronics, music, movies and video games, or Haier producing microwaves and air conditioners, refrigerators. A firm can leave a struggling market more easily or use their larger reserves, from various markets, to help other markets or product lines in difficulty. This is how very large companies, such as Sony, are able to invest huge sums of money and make losses for a long period of time.

B. Internal diseconomies of scale

Internal diseconomies of scale are associated with the output of a company and cause a movement along the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve. If diseconomies of scale are internal to the firm, the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve is rising. There are several ways a company can achieve internal economies of scale, as detailed below.

1. Communication. Small companies have quick, cheap methods – mainly oral. Large companies on the other hand have more costly methods – memos, emails, etc; and these require time to write and read, which may even go unread or be misunderstood. They are also less motivating which can result in inefficiency.

2. Coordination. Larger businesses need more staff and therefore more organizing. This could result in more meetings so everybody knows what to do. Growing firms can also require new ‘layers’ of management. This increases costs and builds another layer of communication. The outcome is even slower decision making, due to the firm’s hierarchy being too tall.

External economies of scale & External diseconomies of scale

A shift of the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve occurs because of internal economies of scale and internal diseconomies of scale. Average costs may change because of external factors. These external factors are beyond the control of the firm.

A. External economies of scale

If economies of scale are external to the firm, the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve will shift downwards.

There may be several reasons for this. First of all, the success of a large industry will be a greater concern to the government, therefore they may, for example, provide TAX breaks, or change legislation making exporting easier, thus cheaper.

1. TAXation. A decrease in TAXation causes a downwards shift. Naturally increasing TAX will increase cost of production and can occur because of a government wishing to limit demand/supply or simply wishing to benefit from a successful/growing industry. On the contrary, an increase in TAX would cause an upwards shift and is an example of an external diseconomy of scale.

2. Technological change. More efficient technology causes a downwards shift. The ability to produce faster, with fewer workers and less mistakes will reduce an industry’s costs.

Example 1: External economies of scale in the long-term production of cars In the North East of England, Nissan, the Japanese car manufacturer, has a factory in a government supported industrial area. There are many companies in this area that supply Nissan with parts such as wheels and glass. This industrial region has government support meaning that buildings and roads built in the area are suitable for industry. There are financial incentives from the government to encourage investment (lower rent, TAX, etc.). Also, labor in the area is skilled with what the company requires thanks to local education and training groups. The close relationship and physical distance allows Nissan to have lower costs per unit through purchase power and low delivery costs. Further costs are saved because of Nissan’s Just-In-Time (JIT) production technique. It involves buying what you need when you need it, therefore raw materials are not held in stock.

B. External diseconomies of scale

The rapid increase in the size of the whole market or industry will lead to an upwards shift. This occurs as a result of companies fighting for resources that have become scarce, including labor. This means providers of those factors of production are able to charge a higher fee.

Example 2: External diseconomies of scale in the long-term supply of IT specialists The shortage of IT specialists happened in the mid-90s when using the Internet became common place and the demand for up-to-date technology increased and individuals with the skill to operate in this area were relatively few in number.

Relationship between Short Run Average Costs (SRAC) and Long Run Average Costs (LRAC)

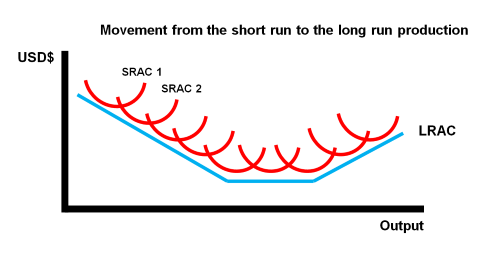

The Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve is derived from short run costs of production.The average cost curve is a U shape in the short run because of the law of diminishing returns. Costs fall and rise because of increasing returns and diminishing returns.

A. Short Run Average Cost (SRAC). The lowest point on the Short Run Average Cost (SRAC) curve is the optimal level of output, the cheapest possible cost per unit. Firms will produce beyond the optimal point in the short run, but not in the long run. Thus the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) cure shows the average cost when producing at the optimal level.

B. Long Run Average Cost (LRAC). The Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve is in fact a collection of many Short Run Average Cost (SRAC) curves. When a firm’s output is more than the optimal level costs will begin to rise. A firm wishes to produce more, but doing so will increase costs. This means it is now time for a firm to expand. In the case of a restaurant, a new restaurant can be opened allowing the firm to expand. The firm now has two shops and is able to produce more. After expansion, some costs are initially fixed, so will have the new Short Run Average Cost (SRAC) curve. This is shown in the diagram below. The cost along the Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve falls, then it rises due to economies of scale and diseconomies of scale.

Summary

Production in the long run differs from the short run because there are no Fixed Costs (FC). The Long Run Average Cost (LRAC) curve represents the lowest possible average costs possible, if running at the most efficient level.

Articles: 1,400 · Readers: 740,000 · Views: 2,209,961

Articles: 1,400 · Readers: 740,000 · Views: 2,209,961